Let’s talk about tokens. When discussing tokens and payments, it’s important to clarify which category of tokens you’re talking about. Today, I’m not discussing NFTs; instead, I’m discussing card network tokens. It’s hard to believe I’ve been writing on this subject for almost 15 years. For a historical refresh, here are a few of my old blogs

- Business Implications of Tokenization (2013 – TCH and 27 member banks were planning to launch their tokenization service and mobile wallet)

- Money 2020: Tokens and Networks (2013)

- Tokens and the Trojan Horse

- Token Vaults (and ApplePay)

- FTC forces MA to Detokenize

- Debit, Routing, Tokens and Liability Shift

- Identity Authentication and Risk

Tokens are not new; merchants have been tokenizing COF for over twenty years (e.g., to comply with PCI DSS requirements). FISV’s TransArmor is just one example of a solution in the market. As I’ll outline below, the power of tokenization has many tiers based on how the token operates and the added assurance it can bring to the transaction. See Wikipedia.

What is a token comprised of?

A token can assign value or substitute one item of value for another. For example, a subway token costs $1, and the fare is $1. You could not use a $1 coin to enter the subway; you had to use a token. This allowed the subway operator to standardize the token acceptance equipment and change the price of a new token without changing acceptance. The token only had value in the subway.

The apparent use of tokens in cards is protecting the primary account number. However, tokens are much more than that. They can have many more attributes and be “bound” to a specific user, device, and/or merchant. A token issued for a particular purpose to a specific user can only be used by that user, thus providing no value to any thief attempting to steal it or re-use it for another purpose.

Example Token Attributes

- Token

- Issued by

- Card Art ID

- Underlying instrument type (ex credit/debit)

- Date of issuance

- Issued to: Person, device, merchant, wallet

- Token Issuer signature/cryptogram

- Token validator (ex token vault, token service, central bank, …etc.)

- Rule set (example Token Acceptance Framework – TAF)

- Token Cryptogram (public/private keys)

- Expiry date

- Revocation authorities

- Customer ID

Enhanced attributes allow Tokens to provide more than just a layer of abstraction. By binding tokens to a specific user or device and using them, they provide enhanced operation (e.g., improved auth rates) and reduced risk (e.g., liability shift) through the unique rules they operate under.

Note: To unlock the power of tokens, well-defined rules, technical standards, operational “binding,” and active governance are needed to coordinate issuance and redemption. This can only be done by networks. While a merchant can tokenize to reduce the risk of data loss, their organic tokenization efforts will not change the rules of how the underlying instrument operates.

Token History – Quick Recap

From 2010 to 2011, there was an explosion of investment into mobile wallets by the likes of Google, MCX and the Carriers with products leveraging “PANs in the wild” to upend the traditional payment model. The Clearing House (TCH) and 27 member banks were also working to create their mobile wallet based upon Padiant (blog) and an organic token service delivered by BellID. PayPal bought Padiant, and Visa acquired BellID. The networks responded by setting up the ”no wrapping rules” to maintain control. The rule’s core is that any token representing a card account must be routed to the network associated with the underlying BIN.

Following this development, V/MA built tokenization services (VTS/MDES) with ApplePay as the first UC (2014). Banks were furious at the networks’ expansion into tokenization (blog), with JPM creating ChaseNet in 2013 (blog) and the networks blocking any expanded use of VTS/MDES beyond Apple (ex, Google could not participate and subsequently built its token network with processors).

In 2015, the issuers directed the networks to enable TCH as the token vault (2016). While MA relented immediately, Visa correctly stated that EMVCo tokens operate under a detailed specification and that token vault operation must align with that specification. Subsequently, TCH joined EMVCo and began work on a token vault specification (2016-17). In 2019, the EMVCo specification was complete, and Visa acquired Rambus (i.e., the BellID platform that provides tokens for both VTS and TCH’s Tokenization System).

Merchant Problems with Tokens

Virtually all merchants have adopted network tokens. A key exception is Walmart. Tokens greatly complicate Walmart’s advanced routing and bilateral clearing. Thus, they work to avoid any token acceptance (e.g., no contactless acceptance). Walmart has also invested heavily (and litigated) in guiding consumers to use PIN for debit and a best-in-class risk/fraud infrastructure (i.e., under 3-5 bps).

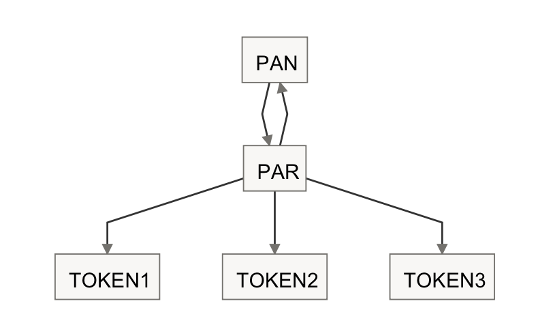

The FTC’s Order to MasterCard regarding debit detokenization is one example of the issues merchants face. Another is the complexity of dealing with multiple tokens from multiple sources for a given customer’s instrument, each with a different authorization rate, rules and cost. Merchants must also track this transaction’s rebates, returns, refunds, disputes and loyalty information. MSPs have developed Payment Account Reference (PAR) systems to map the various tokens and loyalty accounts to a single customer.

From Mastercard “The Payment Account Reference (PAR) is a value linked to the Primary Account Number (PAN) of a Mastercard-branded cardholder account. EMVCo introduced the industry-wide solution to address merchant and acquirer challenges resulting from tokenization. PAR links tokenized and PAN-based transactions without needing a PAN as the linkage mechanism (1:1 PAR to PAN). PAR enables merchants & acquirers to maintain fraud, loyalty and reporting programs dependent on PAN today. “

The PAR represents the common reference to the processor’s proprietary tokenization system, which stores different token types, some from network TSPs and others based on internal systems. For each transaction, processors control how a payment is authorized (i.e., payment optimization) and track how the PAR/Token is routed and approved, as each can entail a different network/processor fee. See MRC Presentation.

In the event of a transaction decline, processors/merchants further fraud-screen the transaction and assess whether to replay it with corrected token assurance information or as an untokenized PAN. This is known as detokenization and resubmission in the industry, or “de and re.”

Tokens benefit merchants by enhancing authorization rates, with Adyen touting a 3% uplift to eCom auth rates for network tokenization. The benefits to wallets with provisioned DPANs are even greater, with Auth rates over 97%. As great as these benefits are, using tokens also has costs based on the merchant’s unique fraud and risk characteristics and any unique routing or bilateral discounts. Thus, the benefits of tokenization must be weighed against the costs.

This leads to yet another financial “optimization” (see MRC reference): Merchants only send high-risk transactions through tokenized flows (where possible). For example, a guest checkout in eCommerce is tokenized, and then the merchant works to obtain the card on file.

I believe this will change substantially in the merchants’ favor as SRC transforms authorization rates (and fixes the many flaws in 3DS).

Tokens Today

ApplePay provides the best example of card tokenization. When the issuer provided the DPAN through the network tokenization service, Apple provided a unique device signature before the DPAN token. Thus, the unique DAF/TAF rules associated with a DPAN only qualify when the token is sent together with the device, which dynamically signs the DPAN for a given use (see Apple documentation).

In other words, the DPAN token is useless without the device. For an overview, see my Provisioning blog and this Thredd doc.

Tokens, when combined with device binding (and subsequent attestations) and rules (e.g., TAF/DAF), drive adoption. In the case of ApplePay DPAN (and GPay), Tokens and Devices provide better fraud and risk performance than plastic (after a valid issuance).

While Europe will succeed in driving Apple to open up the SE, neither the storage of a token nor access to the NFC radio provides the value of ApplePay. It is the binding of device, account and person within a set of rules that creates trust. No iPhone user is going to stop using ApplePay; it’s no longer a payment wallet, as it now holds everything (see Digital Wallets—Core Functions and Competitive Strategies).

Token Assurance – Ancillary Data – Operational View

Moving from the ApplePay DPAN provisioning, let’s talk about network tokenization of cards on file (COF). As outlined above, Payment tokens are not the only data elements that pass within the EMVCo token specs; ancillary data also flows with the token (token assurance information – see Rambus note on EMVCo 2.0 Token Spec and excellent paper by Johns Hopkins – 2016)

Different assurance payloads ride with different transaction types (ex, EMV Issuer Card, Virtual Card, Wallet, Tokenized COF). Token assurance methods indicate the identity and verification (ID&V) type performed in the token provisioning (see Boston Fed and MA processing rules). If the Merchant is the Token Requestor (ex COF), Merchant-related data elements, such as the Card Acceptor ID in combination with Acquirer-identifying data elements, are used to limit the use of a Payment Token by comparing these fields in the transaction processing messages with controls maintained in the TSP (Issuers) Token Vault.

Since we are focused on identity/binding, let’s discuss how tokens and identity interact in “binding.” There are five primary ID&V Types.

- No ID&V

- Valid PAN

- TSP Assurance (Issuer)

- TSP + Requestor Data. Ex Address, IP Address, Device ID, email, ..etc.

- 3DS + Issuer ACS server (w/step-up auth): This has failed due to insufficient issuer effort.

One issue with detokenization is the loss of token-specific assurance information (e.g., ID&V). For example, suppose you had a tokenized debit with Issuer validation. In that case, Issuers are not compensated for providing merchants with verification if they attempt to clear the transaction in a lower-cost network. The ancillary information depends on the card type. Dual message EMV debit cards operating within the CTF/3DS framework carry far more information than a PIN debit. Thus, Assurance data is network-specific, TSP-specific, and rule-specific.

Token assurance information is a hot button as networks set rules but is challenged to mandate “action” that requires wallet, issuer, processor, merchant or consumer investment. For example, mobile platforms have very precise identity information, which includes:

- IMEI

- Biometrics

- Wallet ID

- Location

- Stored cards

- Stored government credentials

- SIM card, phone number

- …etc

Mobile platforms are best positioned to provide assurance separate from payment networks. A recent example is Google SPA.

TSPs/Issuers would greatly prefer platform device assurance data above IP addresses or mailing addresses. The mobile platform must be an economic model for this assurance information to flow. Per eCom 2025, Payment passkey and FIDO will transform e-commerce in a way not seen in 20 yrs. Tokens, binding, FIDO, credentials are all part of it.